In Ps 110:1, in Hebrew, the One and Only YHWH is contrasted with 'adôni (“my lord”). In the LXX translation, we find ho kyrios contrasted with ho kyrios mou. So this is perfectly in line with the usual LXX translation of YHWH with ho kyrios. The key word, for both versions, is: contrasted. However, and unlike Ps 110:1, Paul, in 1Cor 8:6, refers to Jesus as eis kyrios (“one lord”). Exactly as Deut 6:4 refers to the One and Only God, not only in the LXX translation (kyrios eis), but also in the original Hebrew (YHWH 'echad). Now, unless one is ready to resort to the desperate gambit of affirming that there is a (significant) difference between eis kyrios (1Cor 8:6) and kyrios eis (Deut 6:4 – LXX), the two expressions are essentially one and the same.

One may say that what is important about 1Cor 8:6 is the context of the whole chapter 1Cor 8, where Paul speaks to the Corinthians about the right attitude to take regarding the food sacrificed to idols. As is known, Paul had a rather "liberal" attitude about the issue, with the only limit that those who are "stronger" should not cause scandal to those who are "weaker" and have scruples.

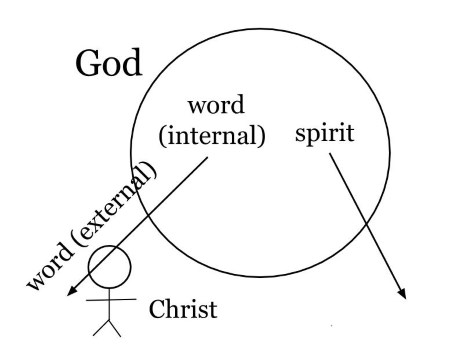

But the text of 1Cor 8:6 cannot be treated lightly: Paul speaks as though the One God (eis theos, the Father) had entirely transferred the title and role of One Lord (eis kyrios, that is the same role that is esclusive to YHWH in Deut 6:4 – LXX) to His resurrected, ascended and glorified Son, Jesus Christ.

Certainly Paul caused scandal among the Jews, and in particular the Judaeo-Christians of Jerusalem, by not imposing the Mosaic Law on Gentile Christian converts. In fact, Paul's "liberal" attitude towards the Mosaic Law was so extensive, that he went as far as affirming that ...

Circumcision is nothing and uncircumcision is nothing. Instead, keeping God’s commandments is what counts. (1Cor 7:19)

But I suspect that Paul's affirmation that (the resurrected, ascended and exalted) Jesus Christ was (had become?) eis kyrios was considered by the orthodox Jews Paul’s peculiar heresy.

Marcellus of Ancyra (died ca. 374 CE) is an enigmatic figure. He was a staunch Nicene, friend of Athanasius, defended by popes but also reviled as a heretic. Eusebius of Caesarea wrote two polemical tracts against Marcellus, Contra Marcellum and De Ecceiastica Theologia

Critics claimed that Marcellus believed that God was a Monad and only emerged as a Trinity for the sake of salvation (page 50). Marcellus was labelled as a Sabellian. Lienhard points out this comes from his opponents and not from Marcellus's own writings. In the end Lienhard affirms that Marcellus was guilty of a bit too much speculation (which he somewhat disavowed in the end) and some inconsistencies in his christological/theological terminology.

One of the useful aspects of Lienhard’s book is that it makes one understand better that the Arian controversy was much more complex than most textbooks let on.

Two passages from Lienhard’s book, in particular, are worth quoting.

What "other ways"? The options are not unlimited. The "Cappadocian settlement" is unsatisfactory (besides being un-scriptural), because it is an unstable compromise, permanently oscillating between tritheism and modalism. Then, what are the other options we are left with?