|

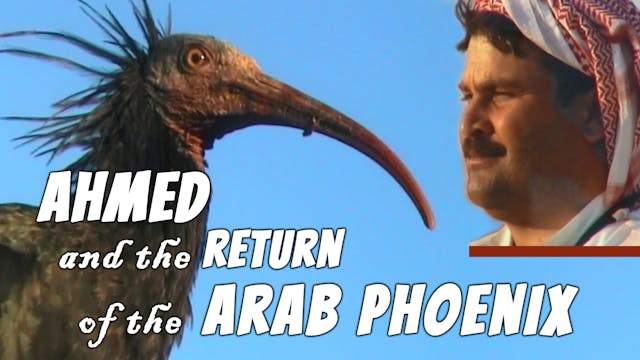

| No, its not Basil with the Arab Phoenix, but Ahmed with a Bald Ibis ... |

Basil of Caesarea (ca. 329 - 379) was the Greek bishop of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia. His brother was Gregory of Nyssa. With Gregory of Nazianzus, the three are collectively referred to as the Cappadocian Fathers.

Some time ago, in his blog Eclectic Orthodoxy, Fr Aidan (Alvin) Kimel wrote a post by the title St Basil the Great and the Search for Hypostasis (14 July 2013).

Here are my notes of comment and criticism. (I suggest that, first you read Fr Aidan's post.)

Fr Aidan Kimel obviously is an apologist, more, an enthusiast of the

Cappadocians. I think they are possibly the worse thing that could

happen to Christianity at the most critical time, so much so that I prefer to call them the Cappadocian scoundrels,

for the mischievousness of their deeds, viz. concocting the doctrine of

the (co-equal, co-eternal, tri-personal) Trinity, which, with good peace

of deluded advocates, was and is nothing but a political ploy, designed

to reconcile, after some 60 years of strife, the (neo) Nicenes with the

(semi) Arians. Sadly for Christianity, they succeeded.

In his post, Fr Aidan says that in 377 CE Amphilochius of Iconium wrote to St Basil and asked him to explain the distinction between ousia and hypostasis. Basil responded with a statement that Fr Aidan reproduces in his post, from Basil's Letter 236 §6.

N.B. Fr Aidan Kimel's quotation does not include the end of §6, perhaps because it was not included in his source (John Behr, Nicene Faith, II, p. 298), perhaps because the omitted part would have been rather embarrassing. Here is the quotation of the omitted part of §6:

On the other hand those who identify essence or substance [ousia] and hypostasis are compelled to confess only three Persons [prosopa], and, in their hesitation to speak of three hypostases, are convicted of failure to avoid the error of Sabellius, for even Sabellius himself, who in many places confuses the conception, yet, by asserting that the same hypostasis changed its form to meet the needs of the moment, does endeavour to distinguish persons [prosopa]. (“Basil the Great on Ousia and Hypostasis”, Letters, 236. 6 @ earlychurchtexts.com; St. Basil of Caesarea, Letter 236 @ newadvent.org)

The above quotation shows how difficult it was, even for Basil of Caesarea, to replace prosopon with his his new-found pet word, hypostasis.

Anyway, Basil may try as much as he likes to explain the difference between hypostasis and ousia

to a perplexed Amphilochius of Iconium. The fact

remains that those definitions are entirely his invention, without the

faintest basis in Aristotle and in previous usage. So much so that John

Behr “suggests that Basil is working with the distinction proposed by

Aristotle between primary and secondary substance”. By this, John

Behr adds to the

confusion, because, the

“particular or individual substance” (say, Paul, or Timothy, or Silvanus) is precisely what Aristotle refers to

as “primary ousia” whereas the “given essence” is precisely what Aristotle refers to as “secondary ousia” (for instance, man).

Athanasius was perfectly aware of this abusive use of hypostasis by the Cappadocians, so much so that he continued to refer to God as "one substance" mia hypostasis.

Around the Synod of Alexandria of 362 (see Socrates Scholasticus > Church History, Book III, ch. 7-8), the Latins tried to translate the Cappadocian formula ena ousia en treis hypostaseis with una essentia in tribus substantiis, and they were horrified, because they perceived it as tri-theistic, through and through.

So as to stop being scandalized, the Latins had to invent a new word to replace substantia, as a translation for hypostasis: subsistentia. But, as the Online Etymological Dictionary appropriately says,

“Latin subsistentia is a loan-translation of Greek hypostasis, "foundation, substance, real nature, subject matter; that which settles at the bottom, sediment," literally "anything set under."” [entry subsistence]

In the concluding remark of his post St Basil the Great and the Search for Hypostasis, however, Fr Kimel is honest enough to admit:

“I must note that my language in the last two paragraphs reflects later Church usage. For Basil, as for Jesus and the Apostles, the one God is the Father.”

Unfortunately, this is precisely the problem with Eastern Orthodox Christianity:

whether they are aware of it or not, they have never let go of (a certain amount of) Subordinationism.

Still not convinced that the Eastern Orthodox understanding of the Trinity is ultimately Modalistic Monarchianism? Then read what Fr Kimelwrites, just before the previous admission:

Still not convinced that the Eastern Orthodox understanding of the Trinity is ultimately Modalistic Monarchianism? Then read what Fr Kimelwrites, just before the previous admission:

"The only difference between the Three is how each is the one God—not a difference in substance but of mode of existence." (St Basil the Great and the Search for Hypostasis, cit. - emphasis added)

You mention that the Eastern Orthodox still retain "a certain amount of" subordinationism. But don't you do that as well (I am not being accusatory; I am genuinely curious)? If the only true God is YHWH, not Jesus, then doesn't that demand at least some form of subordinationism? It seems that you would have to identify Jesus as the very same God as the Father to avoid it.

ReplyDeleteThis is a very delicate point, but here is my answer.

ReplyDeleteJesus is not God, in the sense that he is the One and Only YHWH.

Jesus is not mere man, because in him is incarnated the logos, an eternal, essential attribute of God.

Jesus is therefore God and man, not from eternity, but since he was conceived of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Having being raised, ascended and seated at the right of the power, he is fully eentitled to receive worship.

I see. But if the Logos is an attribute of God (and indeed is God per John 1:1) that became incarnated in the man Jesus of Nazareth, wouldn't that literally make Jesus God? Unless you're saying the Logos stopped being a part of God and fully became Jesus.

ReplyDeleteFor clarification of the above comment: imagine it like a venn diagram. One circle is God the Father, the other is Jesus Christ. If part of the Father (i.e., his Logos) has become incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth, then wouldn't the two circles overlap at some point? Another way to put it: if God's Logos is a part of himself, and the Logos became Jesus, then isn't Jesus part of God?

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete@ Anonymous (31 August 2017 at 17:55 and 18:09)

ReplyDeleteI believe that the relationship between Jesus and YHWH, is best captured in Col 1:15 (without attributing a temporal sense to the expression "firstborn of all creation") and Heb 1:3, although the word logos is not used there. While Jesus is the incarnation of YHWH’s Word/logos/dabar, the logos doesn’t stop being an essential attribute of YHWH, otherwise we would be left with YHWH deprived of His Word/logos/dabar. Which, BTW was the heresy of the alogi (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alogi).

Thanks for your comments. If the Logos continues to exist as an attribute of God and does not actually become Jesus of Nazareth, then how is your position different from the so-called "biblical unitarians" who believe Jesus was a man (albeit a perfect man) indwelt by God's Logos? It seems like if the Logos becomes (ginomai) flesh, there must be an alteration of some kind.

ReplyDeleteI never said that “the Logos ... does not actually become Jesus of Nazareth”. So much so that I expressly affirmed that “Jesus is the incarnation of YHWH’s Word/logos/dabar”. Does it mean that Jesus = YHWH? No, it doesn't: the logos is NOT a person, BUT it (it ...) is an essential attribute of YHWH. That very same logos (NOT a person, BUT an essential attribute) became incarnated (sarx egeneto) in the person of Jesus of Nazareth.

Delete